Whole Wheat Sourdough

Perfectly tender, open crumb with a flakey crust, all while using whole wheat and whole grain flours. This bread tastes great, is great for you, and is so simple to make!

This post may contain affiliate links from which, at no additional cost to you, I may earn a small commission to keep this site running. Only products I myself would or do use are recommended.

FYI, If you’re new to the world of sourdough, check out this post about creating a starter and this post about maintaining a starter. And before baking your first loaf, you may want to check out this post all about levains. And, if need be, check out this post about troubleshooting a sourdough starter. And most importantly, try out my simple, easiest sourdough recipe here!

Why this recipe works

This recipe is simple! It requires minimal mixing, which for me is the worst part of sourdough. It’s also absolutely doable with a spatula rather than your hands, which, to be honest, is why I hate the mixing. I have very dry hands and also often have my nails painted, making it unideal to mix my sourdough by hand repeatedly. Instead, this method requires one step of mixing.

While more artisan style loaves call for using your hands (there are some benefits—most notably a better feel for when the dough is properly mixed), I’ve never found it to make a huge difference. The real key is a healthy starter and overall experience as a bread baker.

This recipe also uses up to half whole wheat and/or whole grain flour. I don’t recommend using all whole wheat until you’re a seasoned sourdough baker. And even then, I don’t care for the taste of an entirely whole wheat loaf, as it becomes too dry and dense. Which is why I use a 75% hydration (water to flour ratio), meaning you’ll have a soft, delicately chewy loaf that’s still easy to work with.

Finally, there is some flexibility in this recipe. You can use your oven to build the levain (the bulked up bit of starter you’ll use in the dough) and for the bulk fermentation (the first rise), meaning it’s faster and more predictable in its timing. Or you can use the counter, which takes longer but requires less rigid watching and timing. And while final proofing the shaped loaf is best done in the fridge (it deepens the flavor and makes the loaf keep its shape better), you can also do that on the counter, speeding up the process.

Overall, this recipe is simple and flexible, making it the easiest sourdough recipe that I love falling back on.

Key ingredients & equipment

Active starter (levain). In the recipe I do walk you through how to build the levain, but you can find out more about levains (which is just active starter that’s bubbly and passes the float test) in this post here.

Warm water—roughly 80F/27C. I suggest filtered water, unless your tap water is particularly fresh and clean, such as mountain areas.

Bread flour. All-purpose flour can work, too, but bread flour is by far the superior choice here.

Whole wheat and/or whole grain flour. For this loaf, I used a combination of whole wheat and whole grain for half of my flour (so 50% bread flour, 25% whole wheat, 25% whole grain). It created a soft, tender texture that was still hearty and grainy like I love.

Salt. I suggest finely ground sea salt.

Large mixing bowl. I always use a large bowl so I don’t spill ingredients as I mix. Things can get messy!

Kitchen scale. Be sure it’s reliable. I highly suggest weighing everything for sourdough, as measuring cups can pack in the flour and cause your ratios to be wildly off. Until you’re experienced, it’s best to carefully weigh ingredients.

Thermometer. Again, be sure it’s reliable. If you don’t have one or it breaks, you can use the boiled water method: bring 2/3 cup water to a boil and add it to 1 and 1/3 cup cold water. This will give you a little more than the 375g you need, but it should be the correct temperature.

Rubber spatula. This makes mixing so much easier, as it’s all rubber and easier to clean.

How to make whole wheat sourdough bread

If you’re new to sourdough baking, I suggest checking out this post here for general timing suggestions and a more detailed breakdown of the process. It may feel daunting at first, but it’s actually a simple series of steps.

1. Build a levain and let it rise until bubbly. Take 25g starter and mix with 50g warm water and 50g flour. Let rise on the counter for 8-12 hours (or in the turned-off oven with the light on for 3-6 hours), until it doubles in volume, has bubbles that break the surface, and can pass the float test (see FAQ’s below for doing a float test). For more on levains and float tests, see this post here.

2. Stir active levain with warm water. I like this order of stirring because it’s the easiest. I just use an all-rubber spatula to mix the two together until mostly mixed. Don’t worry if the starter/levain isn’t fully dissolved.

3. Stir in salt. You can do this with the flour, but I like doing it here to let it dissolve fully.

4. Stir in flours until combined and no dry sections. At first, this may seem way too dry to every mix together. Just keep mixing, using a folding motion with your spatula and occasionally flattening it down in the middle to release any water or flour pockets. You can also use your hands and squish it together between your fingers. Mix until you don’t see any pockets of flour. It will be a shaggy ball that will eventually sink into the shape of the bowl as it rests.

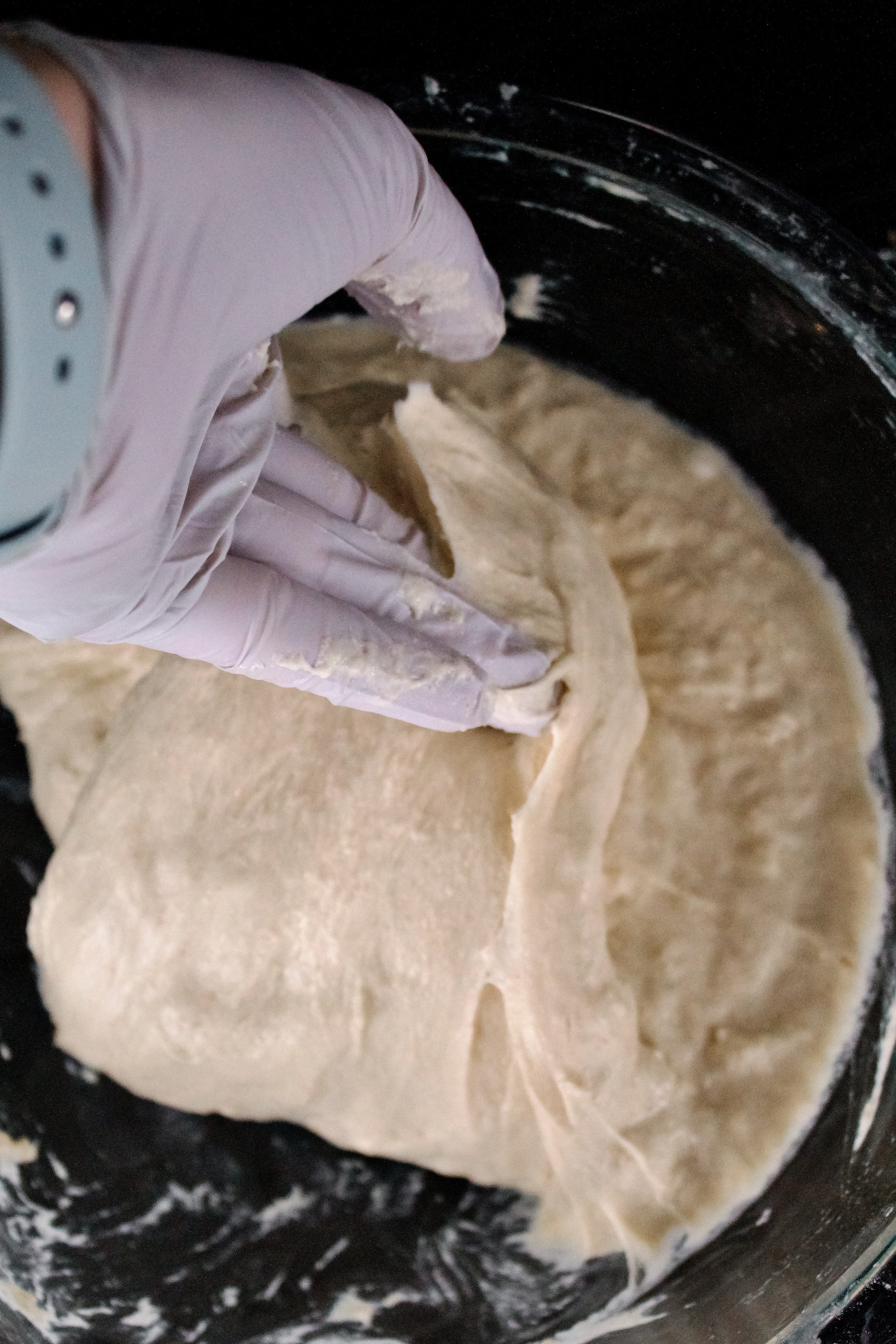

5. Stretch and fold. Let the mixed dough rest for about 30 minutes (a little less or a little more is fine—life happens). Then, using clean, damp hands, slide your hand under one “side” of the dough and grab it gently in your fingers. Pull it up and fold it over the middle of the dough, pressing it gently. It should stretch a little past the middle of the dough. Rotate and do this at least 4 times, until all sides have been pulled up, folded over, and then pressed back into the dough on the other side.

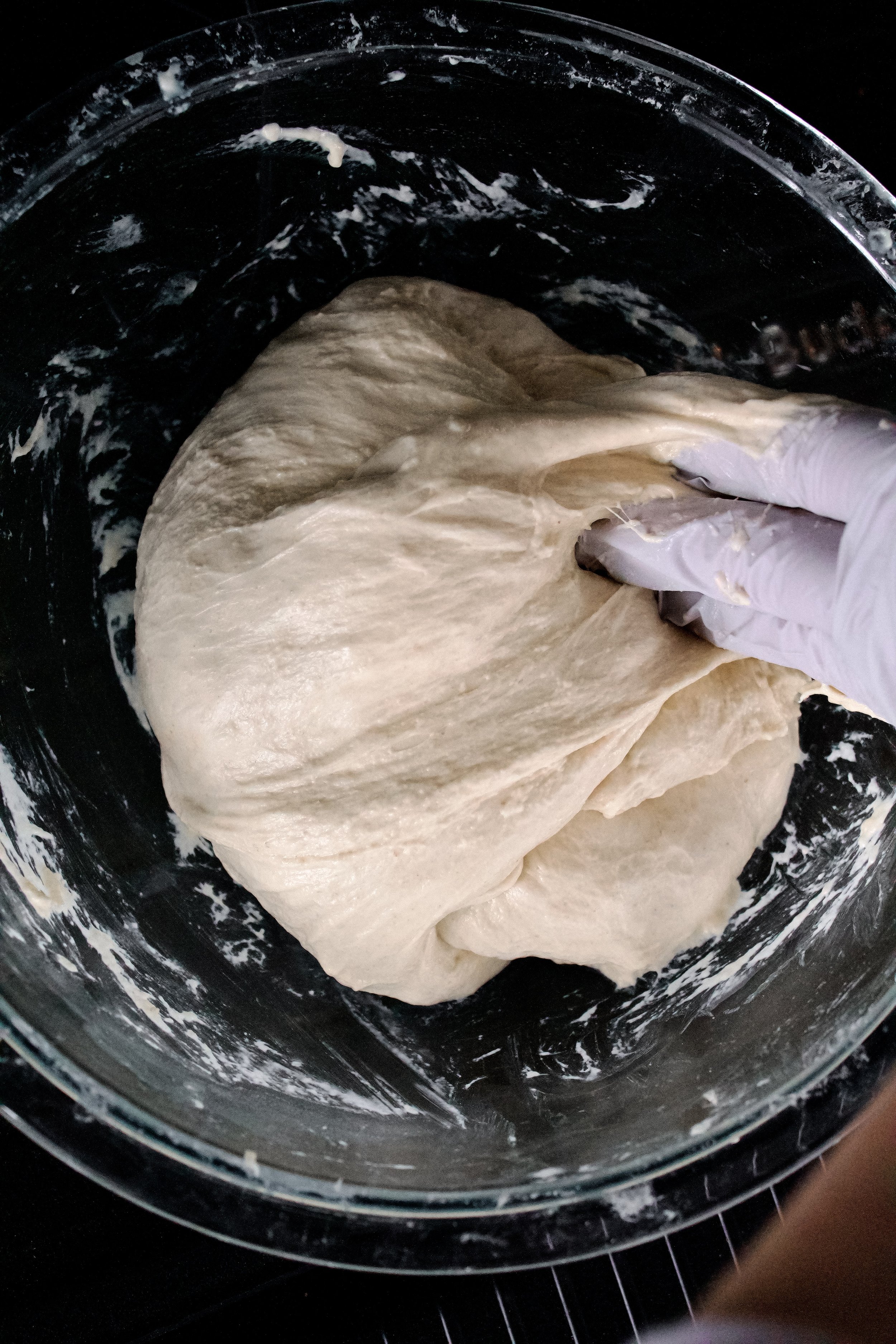

6. Repeat 3-4 times every 30ish minutes. You’ll want to repeat the stretch and folds until the dough is smooth and elastic. It should feel tougher with each set, making it a little harder to stretch and fold each time. The goal is the pass the translucency test—pulling up a small bit of the dough and being able to stretch it until you can see light pass through it without it breaking. Early on, it always took me at least 5 sets, until my starter and technique improved.

7. Let dough rise until volume increases by about 50%. I highly suggest a straight-edged, bucket-style canister with measurements on the side. That will be much more accurate in figuring out how much it has risen. (Note: the photo below shows a double loaf post-rise. A single loaf usually starts at 1 quart and should rise to 1.5 quarts.)

8. Pre-shape. This helps even out the structure and helps build the structure needed to actually shape the bread for baking. Simply fold two opposite sides over the middle (similar to the stretch and folds) then repeat with the other two ends. Flip it over, cover with plastic, and let rest for about 20 minutes.

9. Shape. If making a round boule, you’ll repeat the steps from the pre-shape. Fold one side over the middle, then fold the opposite side over the first fold. Repeat this with the two resulting ends. Flip it over and use the edge of your hands (the sides of your pinkies) to spin the dough as you gently pull your hands under it, pulling the top as tight as possible. Place upside down in a floured banneton (or small mixing bowl lined with a tea towel). If the bottom (which is now facing up) begins to lose its tightness, use damp fingers to pull it back together and stick it to itself. This helps keep that taut surface on the top. Cover tightly (right against the dough and a little around its edges) with plastic wrap.

10. Final proof. Refrigerate at least 8 hours, or up to 36 (I’ve done more, but often the bread gets too puffy by then). Or, you can let it proof on the counter for 30-60 minutes, until it just begins to puff up slightly.

11. Bake. Preheat your oven and baking vessel at 450F/235C. After preheat cycle is done, let it continue heating 10-30 minutes. Remove your bread from the fridge and turn over on a piece of parchment (so that it’s right side up again). Using a very sharp knife, score it as desired (I’m basic and just do slashes). Trim excess parchment and transfer carefully to your baking vessel and place the lid back on. Bake for 30 minutes then remove the lid and turn the oven down to 400. Bake 15-20 minutes more, until your ideal shade of golden brown.

12. Let cool 1 hour. This is pretty mandatory, as the bread will turn gummy and begin to dry out if you cut it too soon.

Enjoy!

Uncut bread can last on the counter 2 days or can be wrapped un foil and frozen up to 2 months. Let defrost on the counter before serving.

Cut bread should be wrapped in foil or plastic.

Timing options:

For a full breakdown of some popular timing options, see this post.

Generally, it takes over a day to make a loaf of sourdough, only spending a minimal amount of time every few hours doing anything to it. If you plan it carefully, you could start early in the morning and have a loaf ready for a late dinner, but the most ideal method is to let the final proof happen in the fridge for at least 8 hours.

How long each step takes depends primarily on ambient temperature. Rise times can vary widely on the counter, depending on the time of year and how warm/cold you keep your house. Using the oven light method (meaning oven turned off but the light turned on) is much more consistent and usually means you can build your levain in the morning and shape your loaf by the evening, letting it proof overnight in the fridge.

For reference, here are the typical times each step takes. Feel free to try out some different Note that some are a wide range on the counter, depending on weather.

Levain

6-12 hours on the counter (up to 18 in really cold weather)

4-6 hours with the oven light

Stretch and folds

2-3 hours (depending on how many you do and how long you wait between each set)

Bulk fermentation (can be slowed down using the fridge, as necessary)

6-12 hours on the counter (up to 18 in really cold weather)

4-6 hours with the oven light

Final proof

30-60 minutes on the counter (not recommended unless necessary)

8-48 hours in the fridge

Baking

About 45 minutes

Cooling (necessary before cutting)

one hour

Tips and FAQ’s for this recipe

What kind of wheat flour should I use?

I used 25% (125g) King Arthur Whole Wheat Flour and 25% (125g) Arrowhead Mills Whole Grain Flour. The actual difference is that whole wheat uses the whole grain kernel of wheat, while whole grain can use any whole grain kernel. I’ve found whole grain usually is grainier. Feel free to experiment, as there are SO many types of whole wheat and whole grain flours out there, and each one can create a different taste and texture.

Can I use all whole wheat flour?

I wouldn’t unless you’ve been making sourdough for a long time. Whole wheat flour is drier than bread flour, meaning a loaf made entirely of whole wheat flour will be denser and drier. This can be balanced by using more water, but this is not an exact science. Thus, I suggest starting with no more than 50% of your flour being whole wheat and/or whole grain. In fact, in my early sourdough days, I only used about 10% whole wheat and then worked my way up to 50%. So feel free to adjust, remembering that your total flour weight should be 500g.

What if it’s rising too fast?

If the bulk fermentation (or even levain) is going too fast, feel free to use the fridge! This will slow down the yeast, giving you some buffer time. However, it’s important to catch it early enough, as the fridge doesn’t stop the yeast from rising somewhat, especially for the first couple hours as it cools down.

What is the float test?

It’s so simple! You just take a very small spoonful of your levain (or active starter) and place it in a cup of room temperature water. If it floats, it’s ready to use in baking. If not, it probably needs more time. Usually, when the bubbles begin to break the surface of the levain/starter, it’s at the beginning of being ready. Once the bubbles fill the surface and it starts to sink back down, it’s at the very tail end of being usable, so watch it carefully (and time your loaf carefully).

Why do stretch and folds?

Stretch and folds build strength into your dough but in a gentle way, creating a more tender loaf. Rather than knead the bread, you’ll simply stretch and fold then let it rest, letting the sourdough work its magic to create those long gluten strands that give the classic sourdough crumb. What I love the most about stretch and folds is that they are easier to monitor than kneading (and easier on your wrists!). Even if you don’t do a full 4-5 sets (I don’t always), it builds just enough strength while still keeping the bread soft and fluffy.

What is the difference between bulk fermentation and final proof?

Both are important to sourdough on a chemical level, but the basic difference is that bulk fermentation is the longer rise that is done first, allowing the dough to build acid (which creates that sour taste) and carbon dioxide for rise and an airiness. We don’t want it to double in volume, because that would exhaust too much of the yeast, leaving none for what’s known as oven spring (the final release of carbon dioxide that makes that lovely ear or slit down the middle).

Final proof is important because the shaping process removes a lot of the gas created in the bulk fermentation. You want to give it a chance to rest, puff up again (just a bit), and ideally build a little more flavor. This is why refrigeration is so helpful. The yeast grows very slowly in the fridge, meaning it won’t rise very much. However, the good bacteria continues to grow and create the various acids that create that sour taste. Still, even without the fridge, this final proof allows your shaped loaf to get some rise, relax, and be ready for baking.

How do I shape the loaf?

You can do any shape you’d like. I often do a round boule or loaf, since I have a dedicated bread pan for each shape. It can often be helpful to watch a video on shaping. Most shaping methods will have you fold one side just past the middle (so about 2/3 over) then repeat with the opposite side, folding that fully over the first fold you made. It’s kind of like doing a trifold on a paper. However, here is where methods can vary. If I’m making a long loaf, I’ll stop there and begin pulling from one side toward myself (using the edges of my hands/sides of my pinkies). It’s kind of like you’re pulling (to create tension against your counter) and rolling/tucking it under (on the far side from you) as you go.

A boule is a lot more straight forward. You do the trifold mentioned above, then repeat that with the two remaining ends. It’ll be somewhat square shaped at this point. Then, take the edges of your hands (sides of your pinkies) and spin the loaf, rotating your hands underneath the dough slightly to help pull the top part tightly. You can do this with either floured hands or damp hands. Damp hands takes more experience, but does get better results. When you turn it upside down into your banneton, try to pinch the bottom together to help maintain that tightness you created. You may need to dampen your hands to do this.

How do I keep the shaped loaf tight?

This takes a bit of practice. I still use flour on my hands to shape my loaf, which means the bottom (where the dough gathers as you pull the top tight) can fill with flour and not glue together. Instead, when you flip it over into your banneton, it will often spread back out. That’s where it’s important to pull it back together, using damp hands to help glue it into place so the taut surface (which is currently on the bottom) stays taut. As well, use that plastic wrap to help keep it in place. I like to tuck it around the edges slightly, keeping the dough from spreading back out and losing its shape.

What should I proof my shaped loaf in?

I’ve used a variety of things. I have a round banneton, a long loaf-style banneton, and some round and oval shaped bowls that I also use. I always line my bowl or banneton wit a tea towel, because it prevents all sticking and we prefer the taste of a crunchier, bubbly crust (see below). While bannetons are cool and all, they’re not necessary, especially for a round loaf since you likely have a comparable bowl at home you can use. If you want to make a loaf or batard, a banneton may be ideal to help it maintain that shape, but even an oval or oblong bowl or serving dish would work.

How do I get a more bubbly crust?

A bubbly crust—which is also much more crunchy—is actually pretty easy to achieve. It comes from omitting flour in the banneton (or towel-lined bowl) and perhaps spritzing the bread with water right before baking. In order to keep the bread from sticking to the banneton or bowl, we usually sprinkle it with rice flour (as it’s finer and less prone to burning). However, if you line either vessel with a thin tea towel, it won’t stick and gets around the need for flour. This maintains the moisture level on the surface, leading to a more bubbly, crunchy crust.

My sourdough tools

Here are my must-have tools I use for making sourdough. Affiliate links provided.

Whole Wheat Sourdough Bread

- prep time: about 30-40 minutes, spread out

- rise/resting times: 9-36 hours (depending on where it rises)

- baking time: 45-50 minutes

- cooling time: 1 hour

- total time: 12-38 hours

servings: 12-16

Ingredients:

for the levain

- 25g active sourdough starter

- 50g flour (can use half whole-wheat if desired)

- 50g water, filtered and roughly 80F/27C

- kitchen scale

- food thermometer

- clean, clear jar (large enough for the levain to double)

for the bread

- 100g levain (active, bubbly starter)

- 375g filtered water, 80F/27C

- 250g bread flour, plus more for shaping*

- 250g whole wheat flour*

- 10-12g salt (sea salt is ideal)

- large mixing bowl

- straight container with measurements

- banneton or medium round bowl with a tea towel

- parchment paper

Instructions:

make the levain

- Place 25g active starter in a medium jar or small mixing bowl.

- Zero out your scale (or the “tare” button) and add 50g warm filtered water, about 80F/27C. Stir with a small rubber spatula or spoon until mixed well.

- Zero out the scale again and add 50g flour. You can use any combination of flours, but it you are just starting out, you can play it safe with all-purpose or bread flour.

- Mix well, ensuring there is no dry, unmixed flour and no visible lumps of flour.

- Set the lid loosely on top of the jar or cover with plastic wrap.

- Store in a spot with moderate temperature (roughly 70F/21C) for 8-12 hours, until it has doubled in volume, bubbles begin to break the surface, and it can pass the float test. Alternatively, you can place it in your turned-off oven with the light on and let it rise for 3-6 hours, depending on climate and the age of your starter. See this post for suggestions on how to time your levain and dough.

make the bread

- Once the levain is bubbly and active and passes the float test (see note above), you can begin mixing the bread dough.

- Add 100g active levain/starter to your mixing bowl. Add 375g filtered water that is roughly 80F/27C. Don’t stress if it’s a little warmer or a little cooler. Mix until starter is mostly mixed in.

- Add salt and stir well.

- Add the bread flour and mix until fully combined. Eventually, it becomes hard to stir. At this point you could use your hands or you can simply use the spatula to somewhat fold the dough together (literally scooping from the edge and folding it over the middle section). Mix until there are no pockets of dry flour. It should be a shaggy dough at this point.

- Cover the bowl with plastic wrap or a damp towel. Let sit on the counter for roughly 30 minutes (at least 20 but no more than 40). At this point, perform the first set of stretch and folds.

- Stretching and folding is actually quite simple: Using a clean, damp hand, slide your fingers under one “side” of the bowl and grab that section of dough gently in your hand. Lift up gently to stretch it slightly, folding it over the middle of the bowl. It should reach the other side of the bowl or close to it. Rotate the bowl 90 degrees and repeat, until you have stretched and folded all 4 “sides” of the dough. Depending on the size of your bowl, you may need to do 5-6 stretch and folds for each set. Once done, cover again and let sit on the counter.

- Repeat this process every 30ish minutes, for a total of 4-5 sets of stretches and folds. You’ll know the dough is ready for the next step when it is smooth, elastic, and becomes more difficult to stretch and fold. As well, you can use the translucency test: pinch a little piece of dough and pull it up until some light can pass through the middle. If light passes through without it breaking, it’s ready.

- Bulk fermentation. Once you’ve done 4-5 stretch and folds and the dough is smooth and can pass the translucency test, cover it and place in a warm spot (no hotter than 90F/32C) until it has risen in volume by 50%. It should begin to be wobbly at this point. To make this easier, I suggest using a straight edged vessel so you can better tell when it’s risen 50%.

- An ideal spot for bulk fermentation is your turned-off oven with the light turned on. However, if you don’t want it to be ready too quickly, you can use the counter. If it is rising too quickly, feel free to put in the fridge to slow down the rise until you are ready to do the shaping.

- Once it has risen by 50% and is wobbly, gently dump the dough onto a floured surface. You can use bread flour or all-purpose. Pre-shape it by pulling one side up and over about ⅔ of the way. Pull the opposite side up and over the first fold completely (similar to creating a trifold for a piece of paper). Repeat this with the other two sides. Gently flip the dough over, cover with plastic wrap, and let rest for about 20 minutes.

- Now shape the dough. If using a round banneton or bowl, you’ll create a round boule. If using a bowl, line it with a tea towel. Optionally, you can sprinkle it with rice flour or bread flour, but this is not necessary unless you want that rustic, floured look and texture. If using a banneton, you must sprinkle it with rice or bread flour. You can also line a banneton with a tea towel to make for easier removal, and this makes sprinkling the flour optional.

- Remove the plastic wrap from the pre-shaped dough and flip the dough over. Repeat the process of folding one side over then the opposite side, finally folding the two remaining sides to create a somewhat square shape.

- Next, use the edges of your hands/sides of your pinkies to spin the dough while simultaneously sliding your hand somewhat underneath the dough. This is best done on a non-floured surface, but it can be difficult to work with and stick to your fingers. You can use either floured hands or damp hands (oddly enough) to do this. As you spin the dough it should create tension on the top and pull it tight. Keep spinning until the top is as tight as possible.

- Flip the dough over and place upside down in the prepared bowl/banneton. To prevent it losing its shape right away, pull the edges of the bottom (currently facing up) together and use damp fingers to press it together, helping keep that tight surface you created on the top (currently facing down). Cover immediately with a piece of plastic wrap, tucking it slightly along the sides to help maintain the shape you created.

- Final proof. Place the bowl/banneton in the fridge. If using a banneton, it’s best to place that inside a plastic shopping bag and tie the handles to prevent the dough drying out. Refrigerate at least 8 hours, up to 36. You can technically do the final proof on the counter for 30-60 minutes (until it’s puffed up every so slightly), but this can lead to a flatter loaf.

- When ready to bake, preheat your oven to 450F/235C. Place your baking vessel inside the oven to preheat as well. I like my Emile Henry bread pot, but a dutch oven or large cast iron with a lid works, too. Let that preheat for at least 10 minutes after the oven reaches 450F/235C. This allows everything to be properly heated up.

- Once the oven and baking vessel are preheated, remove the loaf from the fridge. Remove the plastic wrap and turn it over onto a piece of parchment paper. Use a very sharp knife or bread lame (a razor for bread) to cut at least one slash through the dough. You can get fancy or just do something simple.

- Cut the excess parchment, leaving just enough of an edge to grab it. Remove the baking vessel from the oven and carefully transfer the dough to it. Replace the lid and bake for 30 minutes.

- After at least 30 minutes, remove the lid and turn the oven down to 400F/205C. Let continue baking 15-20 minutes, until the top is nicely golden brown. If you want a lighter top, it’s best to leave the lid on a little longer then reduce how long it bakes without the lid, so that it still bakes for a total of at least 45 minutes.

- Remove the bread from the pan and remove the parchment. Set on a wire rack to cool at least 1 hour. Cutting a loaf before it’s cooled sufficiently does alter the texture, so be sure to time it carefully.

Enjoy!

*I used 125g whole wheat flour and 125g whole grain flour. If you are new to sourdough, I suggest starting with more bread flour, such as 400-450g bread flour and 50-100g whole wheat (always ensuring a total weight of 500g flour). You can increase the amount of whole wheat over time (proportionately reducing the amount of bread flour), until you find a ratio you like best.